Inflation Makes Mess in Japan, Batters Yen. BOJ’s Kuroda Clings by His Last Fingernail to “Transitory”

But he’ll be out in April.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda, the architect of Japan’s crazed money-printing binge under the economic religion of Abenomics, which started in 2012, will depart the BOJ when his term ends in April 2023. He won’t do a U-Turn on his interest-rate policy because it has been his baby for 10 years, no matter what happens to inflation, and it’ll be up to the next person to deal with this mess. And a mess it’s starting to be.

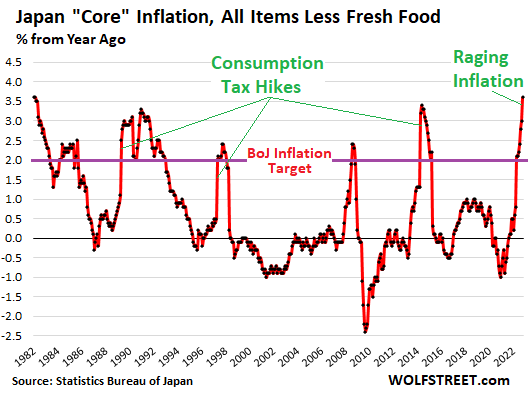

Japan’s “core” Consumer Price Index for all items less fresh food – which the BOJ uses for its inflation targeting – jumped by 0.6% in October from September, according to data from Japan’s Statistics Bureau today. This amounts to 7.4% annualized. The 0.6% jump was the worst month-to-month jump since the consumption tax hike in April 2014; and beyond that, since May 2008; and beyond that, since the consumption tax hike in April 1997.

On a year-over-year basis, the “core” CPI jumped to 3.6%, the worst since 1982, even outdistancing all the consumption-tax-hikes. The purple line indicates the BOJ’s inflation target. As inflation shot right through that target in April, the BOJ has been unwavering in keeping its short-term policy rate at -0.1% and its 10-year yield peg at 0.25%, which is just crazy.

Kuroda, upon seeing the spike in core CPI, said today that it was rising “quite a bit,” and clinging to the “transitory” theory with his last fingernail, he said that it would drop below 2% in the next fiscal year, which starts in April, as the impact of prices of fuel and raw materials fades. But as we’ll see in a moment, inflation has already transcended fuel and raw materials and has spread deep into the economy.

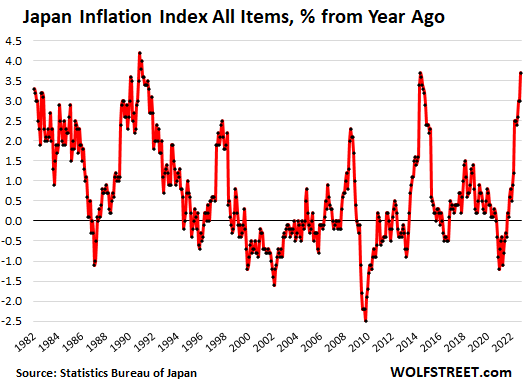

The CPI for all items jumped by 0.6% month-to-month, and by 3.7% year-over-year, matching the consumption-tax spike in May 2014, and beyond that, it was the worst increase since 1990:

The end of the era of true price stability.

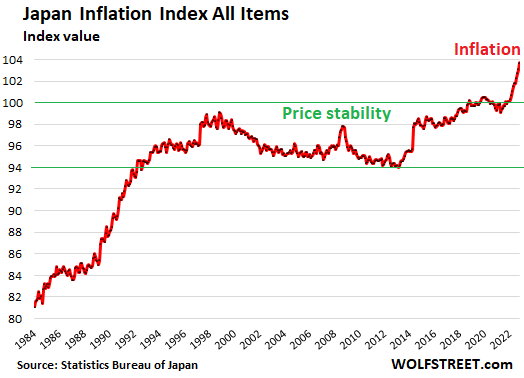

Inflation is particularly insidious in Japan were something like true price stability has reigned for 23 years, where bouts of inflation were followed by some mild drawn-out deflation, to where prices overall remained roughly level for 23 years. People, society, and the economy are not at all prepared to deal with inflation.

Over this period, the Consumer Price Index for all items – as an index value to reflect price levels, not year-over-year change – had been relatively flat. After the consumption tax hike in 1997, the index settled at about 99. Over the next 13 years, the index then declined by a total of 5%, then rose again, reaching 100 in 2018, and roughly remained there until late 2021, when inflation took off.

Some of the major categories of inflation.

- Food: +6.2% year-over-year: fresh food +8.1%; fish and seafood (crucial in Japanese cuisine) +13.9%; fresh vegetables +6.7%.

- Energy: gasoline, electricity, piped gas to the home, propane, kerosene: +15.2%.

- Household goods, such as furnishings, appliances, utensils, bedding: +6.9%.

- Repaid and maintenance: +6.9%

- Communication: +5.6%

- Clothing and footwear: +2.5%

- Rent: 0% (that’s nice)

Governments hold down inflation with categories they control.

- Healthcare inflation: In this system of universal healthcare, the government largely decides what consumers have to pay:

- Medical care: +0.2%

- Medicines: +1.3%

- Medical supplies and appliances: +0.1%

- Medical services: -0.3%

- Public transportation: +0.3%

- Education: +0.7%

- Water & Sewage charges: -3.4%.

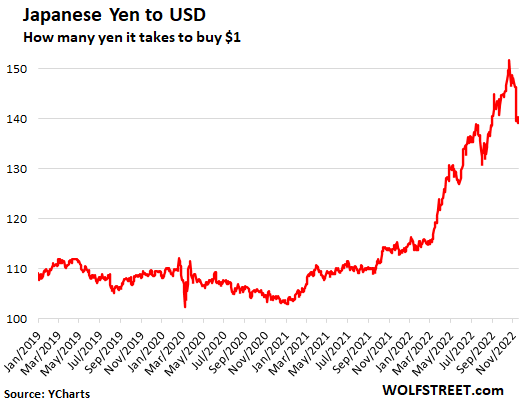

BOJ buys yen to prop it up, after it got battered by BOJ’s let-her-rip inflation policy.

In mid-September, as the yen was in free-fall against the USD, the BOJ started periodic operations of selling dollars and buying yen to support the currency that way, instead of hiking its policy rates to get a grip on inflation, which would cure the yen’s problem.

A plunging yen makes imports of all kinds more expensive, not just raw materials, food products, and energy, but also consumer products and components for manufacturers.

While the plunging yen helped translate foreign-currency revenues by Japanese companies from sales overseas into higher yen figures, it had no actual impact on revenues from products that Japanese companies make overseas and sell overseas, such as automakers that all have plants in the US, Mexico, China, and Europe. And much of what they sell in these markets is made in these markets, not in Japan. A weaker yen doesn’t actually help these manufacturers, but it allows them to translate their sales in dollars, euros, renminbi, and pesos into more collapsed yen, which looks better in yen.

But they’re groaning under rising costs for products they sell in Japan.

In January 2021, it took about ¥104 to buy $1. By last month, it took over 150 yen to buy $1. Today, it was 140 yen to the USD. The large drops over the past two months are likely the result of BOJ interventions:

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

Source link